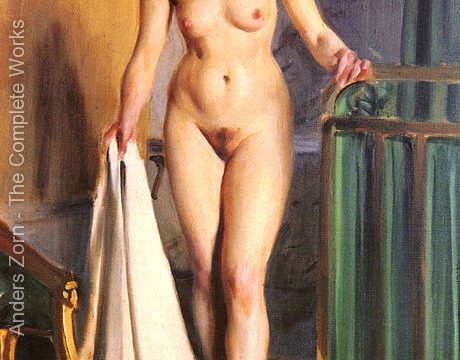

Swedish born Anders Zorn (February 18, 1860 – August 22, 1920) is an artist who will stop you in your tracks with awe. Such simplicity in his strokes while at the same time such volume and character.

This is art that will make you immediately think.

Righly so, Zorn is one of Sweden’s best known artists.

It’s messy and it’s diverse and it’s cunning and it’s deep. I think the most outstanding thing for me is the natural feeling the surroundings have in the paintings. It feels as though the subjects are at home.

It is clear to see the pride Zorn had in his homeland, and reading about his life, it’s also very evident. In 1896 the Zorn’s decided to move back to Sweden from Paris. They bought land and old cottages in Sweden, and together with his wife established a reading society, parish library, a childrens’ home, the Mora domestic handicraft organization, and a folk music revival that still lasts till this day as one of the most prestigious Folk Music Awards in Sweden.

Zorn had a lot of international acclaim in his life, both for painting and etching, and received many quite amazing opportunities to do portraits of quite prominent members of society. At the Paris World Fair in 1889, the 29-year-old Zorn was awarded the French Legion of Honour. In 1893, the Columbian World Fair was arranged in Chicago of which Zorn was chosen as the superintendent of the Swedish art exhibition. Again, this resulted in many commissions, notably of Presidents: portrait of Grover Cleveland and his wife (1899, National Portrait Gallery, Washington DC), an etching for Theodore Roosevelt in 1905, and a painting of William Taft (1911, the White House). Swedish noteables included many members of the Royal Family, including Queen Sofia (1909, Waldemarsudde, Stockholm).

Froknarna Salomon (The misses Salomon) by Anders Zorn